It’s always more entertaining to set out for foreign lands when you’ve got a clear idea of what you’re looking for. And it’s even better when you have the extra task of solving a mystery.

A well and clearly formulated question may often be the very best motivation of all for striding into unknown territory. And it often serves as the proverbial compass needle pointing in the right direction, eliminating ubiquitous dead-ends.

I have fielded questions like, “Do you know tea from Taiwan? What about Tung Ting? What a fragrance, eh?”

Because I was only familiar with a rather skimpy selection of teas from the island that was called Formosa for years thanks to its scenic beauty, I decided to expand my tea horizon. I also wanted to end the age-old dispute over whether the intoxicating fragrance of lilac and peonies ingeniously conceal in the little balls of rolled-up leaves is a natural consequence of expert processing or is added subsequently.

The Background Lies in Fujian

I first came across the name Tung Ting during my second visit to China, when I headed for the southeastern province of Fujian. There, I mapped the production of partially fermented Minan teas (Minan is the name of the southern half of Fujian, which is famous for producing partially fermented teas such as Tie Guan Yin aka Iron Goddess, Huang Jin Gui, Bao Zhong, Wu Long, while Shi Xian, Bai Mu Dan, and Show Mei are produced in the northern part, Minbei). Besides the loose teas which are commonly available in sundry grocery stores as well as souvenir shops, the celebrated Tie Guan Yin can be bought at entrances to Buddhist monasteries or temples where they are displayed right next to incense sticks and smiling porcelain figures of the Laughing Buddha Mi Le Fo. The quality, however, is very problematic and debating the topic of freshness or authenticity with the local merchants is pointless. Pose a question about the harvest period and even a layman will recognize that the merchant doesn’t know because he basically doesn’t care. But I did.

My trip to China led me to a magnificent food trade fair in neighboring Canton, which is held every year in mid-April and offers a unique opportunity to meet with the largest selection of teas from the entire “Middle Kingdom” in one not-so-large pavilion. Here one can meet all the major tea producers and exporters, thus saving lots of time and money instead of making complicated and many times adventurous trips to their home manufacturing operations. And so I visited dozens of stands of various tea merchants only to learn that the best tea was – surprise surprise – being sold right where I was. I was assured that the competition isn’t competitive and, above all, that nothing was a problem. Anyone can produce any kind of tea. Obviously! “No, no, no! Far from it,” I told myself, “they should all do what they do best, and not meddle in others’ crafts.” And I remembered the huge disappointment I experienced while tasting the teas – imposters – that were offered to me on my travels through China’s tea-producing regions. Long Jing harvested and processed in Sichuan is bitter as wormwood, and is absolutely devoid of the hint of honey in its authentic namesake from Xi Hu Lake near Hangzou. Bi Luo Chung produced in Fujian lacks the typical bitterness for which the original tea from Tai HuLake is coveted and equated with gold.

Experimenting with tea flavors is not advisable. I resisted the temptation to bring new names, stories, and flavors home to Europe, and thereby mix the proverbial palette and completely confuse those who have already started making headway in the spectrum of tea fragrance and flavor undertones. That’s what others do, not me. I attended the exposition, created and strengthened trade relations, and, with pockets full of samples and business cards, headed off to neighboring Fujian to have a look at the processing of partially fermented oolongs from the south of the province. It did not occur to me that these teas still weren’t being harvested in mid-April…

Believe It or Not, as You Please…

When you ask passers-by in China for directions, nine times out of ten, each will point you in a different direction. But no need to get annoyed. They’re not doing it to be mean or to make your life difficult. After some time, I got the feeling that, for whatever reason, they were ashamed to say, “I don’t know, I’ve never heard of it.” And so in posing the simplest question one learns not only where the place lies, but often also why it lies there. A new legend is usually born, and whether you believe it or not is only up to you. It is good to ask at least two or three more random passers-by, then analyze their answers and base your decision on the most convincing arguments. For the most part, those are orientation according to maps and the sun, provided it emerges from the steamy mist that usually prevails when fresh teas are being harvested.

The Chinese have a talent for believing the authenticity of their narrations and for regarding them as truth even when they are making up their content. The feeling that it could be that way is so strong that you simply believe it and accept it as reality. So don’t be surprised that, before another bitter experience, I, in a word, naively believed an eight-hour journey along dusty, rocky roads to the mountains in the south of the province wasn’t in vain. That I’d see there somewhere how they roll world-famous Tie Guan Yin, Huang Jin Gui or Bao Zhong oolong teas. Of course I had no idea it was closed there! I was to have that experience much later, a fact that had already been inscribed in my tea destiny long before.

When I evaluated the success of my Fujian mission in hindsight, I frankly wasn’t too satisfied. But what I did regard as a huge benefit was the distinctive, sweet, peony-lilac fragrance that stuck in my nose while drinking an extraordinary, lightly fermented tea called Tung Ting. I bought that in a small tea shop in the province’s capital city Fuzhou and discovered it was imported from Taiwan. I believed it!

Protect, but Don’t Harm!

The history of the charming island of Formosa is more interesting than it might seem at first glance. Separated from the Chinese mainland by a hundred-kilometer ribbon of sea, one would think its populace, history, and culture would be very similar, if not the same. But that was not always the case.

According to the surviving relics, the island was inhabited tens of thousands of years ago. But the natives were not ethnic Chinese, they were islanders who sailed there from the Pacific. It was not until the beginning of the 15th century A.D. that a great number of emigrants from Fujian moved to the island, which was always slightly outside the main interest of China’s populace. The residents of today’s FujianProvince have always been keen travelers, and so it is no surprise the new fertile territory a ways “across the water” attracted their attention.

Neither did it escape the attention of Portuguese sailors who anchored here in 1517, and, thanks to its beauty, named the island Ihla Formosa or “Beautiful Island.” After that, history gained momentum. In 1624, the island was occupied by the Dutch, who founded the original capital city of Tainan in the western part of the island. But two years later, the Spanish seized control, only to be driven out by the Dutch again in 1641.

No local army capable of withstanding the supremacy of the colonizers or other powerful neighbors was ever formed in Taiwan, and so events on the neighboring mainland soon weighed in on the island’s development. In the middle of the 17th century, some 35,000 soldiers from China’s victorious Manchu Dynasty (aka Qing or Ch’ing) descended on the island and began persecuting fleeing supporters of the Ming Dynasty. Thanks chiefly to their military might, the Dutch were driven off the island in 1661.

From then on, as a result of migration of the populace from neighboring Fujian, Formosa began taking on the character of its larger and more powerful neighbor – big China.

The Chinese-Japanese War did not devastate Taiwan much, as the battles were mostly fought on mainland China. Nevertheless, in 1895, Taiwan was surrendered to victorious Japan as war booty. Although Japan brought law and order to Taiwan, it also brought cruel treatment. That resulted in many local residents rising up against the Japanese reign. The locals even managed to briefly declare an independent republic, the first in Asia. But it didn’t last long, as the Japanese quashed the uprising by extremely brutal means. Taiwan became a part of Japan, and agricultural and economic growth set in. The Japanese built roads, railways, schools, and hospitals. They were also pivotal in developing agriculture on the island. Although many Taiwanese were recruited in the Japanese army during World War II, the island itself was not too damaged by Allied bombing at the close of the war. Nevertheless, by that time, Taiwan, like neighboring Japan, was in economic ruin.

China’s last imperial dynasty, the Qing Dynasty, fell in 1911. As the leader of the national rebellion, Dr. Sun Yat-sen was largely responsible for that, and he became the first president of the Republic of China. To his misfortune, he was afflicted by insufficient desire for power and was soon replaced. The subsequent period of civil war, when groups of local warlords fought each other in attempts to seize power, came to an end with the rise of the nationalist army led by General Chiang Kai-shek. The civil war was suppressed, nevertheless, the Kuomintang, or Chinese Nationalist Party, headed by Chiang Kai-shek soon came under threat again.

After Japan’s defeat in World War II, China gained control of Taiwan, which was confirmed by the Yalta Conference. The Taiwanese themselves were happy to see Japanese dominion come to an end. But their joy did not last long. Chiang Kai-shek appointed the corrupt and incompetent General Chen Yi as Chief Executive of Taiwan. That spurred another wave of unrest, this time by the local anti-Kuomintang forces. That rebellion ended with a devastating massacre in which tens of thousands of civilians died. That day, known as 2-28 (according to the date of the tragedy in 1947), became a black mark in the land’s modern history.

In mainland China, however, the communists seized power at the end of the 1940s, and the Kuomintang, still led by Chiang Kai-shek, was forced to retreat to Taiwan. At that time, around half a million Chinese, including 600,000 soldiers, emigrated to the charming island, whereby the population swelled to seven and a half million. But even that strong populace was unable to repel the anticipated invasion of the Communist Army. The whole conflict was ended by the United States, which sent its army to the strait between mainland China and the island to predestine the island’s future orientation.

But Where Did the Tea Come From?

Equipped with information on the enchanting island’s turbulent history, I stand in front of the National Museum of History in today’s capital, Taipei, and I’m looking forward to going inside. I learn that the exodus of one and a half million Kuomintang supporters brought to the island not only China’s intellectual elite, but also an enormous amount of historical objects. This fact places Taiwan’s national museum among the most remarkable in the world. Assembled here are some 700,000 Chinese artifacts. The exhibition halls are situated in the depths of a mountain, which should protect them in the event of a nuclear attack on the capital. The exhibition space is limited, so “only” 15,000 objects may be exhibited at once. These change every three months, which means you could see them all in just under twelve years (if visiting the museum regularly).

“I don’t have that much time!” I say to myself. I study the signboard by the elevator hoping at least one floor will be dedicated to tea culture. But I don’t find even a mention of what is so tied to the history, culture, imperial court, literature, and bohemians, poets, and even ordinary farmers in neighboring China. You probably won’t believe me, but in the entire museum I found just one teapot, accompanied by information that it had been used to prepare tea! And I didn’t even cheat – I passed by all 15,000 exhibited objects!

I leave and it doesn’t even occur to me to return in three months. Imagine, next time there might not even be one tea-related artifact on display…

I expected to learn the most enlightening information about the history of tea in Taiwan in its national museum, but I’ve got hard luck. Then again, why should they have something so specific here, when there’s a museum devoted solely to tea on the outskirts of Taipei in a place called Ping Lin!!!

Not-so-long History

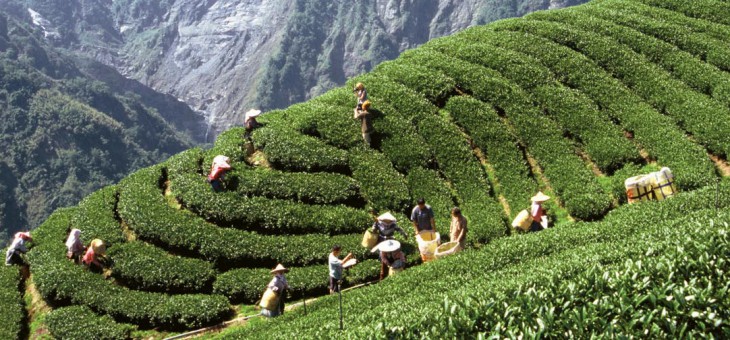

I’m traveling in a suburban bus weaving along narrow hairpin bends, and my heart is rejoicing. Tea gardens appear on the mountainsides, harvest is in full swing, and the weather is agreeable. Although it is almost the end of April, when precipitation climaxes in this part of the island and it rains almost non-stop, today the clouds broke and the sun is shining. But the bus stops relatively frequently to let other cars pass in the other direction. As it does so, it is avoiding huge green tarpaulins stretched over one whole lane of the road. “What is this?” I’m thinking just as I see it. Freshly-picked tea leaves are being spread out on those tarpaulins and left to wither. It is quicker, more effective, and less laborious than handling them in attics under rooftops when it rains outside.

I step out of the bus and ask the way to the museum. I expect it to be a large, several-storey building, but I am wrong. It is comprised of several small pavilions, ingeniously melded into the terrain, and adjacent to it a Chinese garden with a pond full of colorful fish, a little bridge, a gazebo, and a spate of gorgeous plants. Now this is my kind of place.

The information I obtain here adds another dimension to my journey. Not only did I learn who was the first to bring a young tea plant to Taiwan, but also where he planted it. And I can’t miss out on seeing that.

Traces of the history of tea cultivation in Taiwan are quite scarce. The first surviving mention dates to 1661, when European seafarers recorded that the natives drink a beverage made from tea leaves. They did not cultivate the plants, however. They picked the leaves from wild bushes.

Another preserved mention is from 1697 about how the Dutch planted tea plants around the city of Puli in Nantou County and the tea was reportedly even exported to faraway Persia.

But tea planting did not start booming until the mid-1800s. In 1855, a certain Feng Chi Liu returned from the Fujian province after taking his examination to become a civil servant and brought with him 36 tea plant seedlings, which he planted in his native village of Luku in mountainous NantouCounty. Twelve of the seedlings took root and the basis for Taiwanese tea production was established.

Then and there, I knew the small rural community of Luku was a place I had to visit.

Kung Fu on a Stump?

But before that, it was time to explore what was being harvested and processed all around me in Ping Lin. Practically every house along the road is a teahouse or tea shop with a small tea manufacturing operation in the back. My curiosity piqued, I enter a shop and I’m already ensnared by the owner, who very willingly explains what exactly is being done here.

The tea I was treated to is called Tie Guan Yin. It is not produced in other parts of Taiwan. I am thrilled because the method of processing this partly fermented tea had been a mystery to me till then.

I observe in silence and take notes:

After withering for a short time, the leaves, which had been spread out on screens, are enclosed in white cloth and tightened into packages the size of a blow-up beach ball, which are placed in special horn-shaped presses. Here, with a circular motion, the package is continually tightened and the leaves inside are rolled into wrinkled ovals. In light of the fact that they wait to harvest this tea – unlike other quality teas where only the tips of the buds and at most two leaves are harvested – until five perfectly developed blooming leaves appear at the end of each twig, this process is relatively demanding and must therefore be repeated. The man of the house, who guides me through the house, points out that there are many factors – such as the outdoor temperature, humidity, and the quality of the leaves themselves – which determine how many times the white cloth is unwrapped. The damp leaves are released from it and dropped into a rotating drum, where they tumble around as warm air is introduced, only to be tightened up in the cloth again after a few minutes and enclosed in the “horn-press.” This process may apparently even be repeated up to twenty times! Well, how about that!

Now I understand why Tie Guan Yin leaves often lifted up the lid of the teapot from my Kung Fu tea set – they are rolled up very skillfully and once covered with hot water they have a tendency to return to their original shape. I learn that the last step, which has the greatest impact on the dissimilarity between the flavor of Tie Guan Yin and Taiwan’s traditional and probably best-known tea, Tung Ting, is the intense final drying, which could almost be called roasting. It takes place in small ovens, like those in which baguettes or rolls are baked in small bakeries.

I sit myself down on a “stump,” which is the local substitute for a chair, and let the symphony of flavor and fragrance called Kung Fu Cha (also known as Gongfu Cha) start playing on the table, which is naturally also a stump. The tea ceremony in Taiwan has nothing in common with its counterpart in neighboring Japan. The tea isn’t prepared from powder or whisked, and there’s not even a need to seek a special environment with displayed Tatami mats or kneel with humility. Kung Fu Cha tea ceremony in Taiwan usually takes place on stumps, which are not only very carefully chosen (they must meet the strictest artistic criteria), but also crafted with exceptional skill. They can be purchased in special shops with other tea accessories and it should be mentioned that purchasing them means a fairly hefty investment. But not everyone can afford one. However, having at least one such stump and treating a visitor to tea at before offering tea for sale is a given for almost every tea shop.

The Kung Fu tea set itself contains a number of interesting properties, the most important of which is a double-bottom tray for catching excess liquid, a small teapot for infusing the tea leaves, a small vessel similar to a creamer, into which the brew is strained, and a set of miniature cups, one of which is cylindrical and the second, shorter, one rounded. Also required is a set of wooden utensils – tongs, a funnel, a tea needle, and a scoop, which are used very adeptly, especially when something goes awry or to keep the master from being scalded. The preparation itself deserves its own essay. But what every partaker in Kung Fu Cha must know is that the tea is not drunk from the taller, tubular cup into which the master pours it, but rather from the other cup. Through a skillful trick involving the taller cup being covered with the shorter one, both being turned upside down in the master’s fingers, and the liquid left to spill over into the bottom cup, the intensive fragrance is retained in the narrow, upside-down cup. The scent can then be taken pleasure in at will, while the brew in the second cup cools down. I say – like a dream!

After being served oolong on a stump, I’m not surprised by anyone willing to pay enormous amounts (reportedly as much as 100 dollars) for a 50-gram package of the highest quality Taiwanese oolong. I too was treated by the lady of the house and then bought several packs of vacuum-packed “Goddess of Mercy,” of course in a reasonable price range. As I learned back in my hotel room a bit later, it had nothing in common with the brew I’d been served earlier. But who knows why. Perhaps the stump was missing.

Everything Green and That’s That!

From literature I learn about the center of production of green teas around the city of Sansia, which lies 30 kilometers southwest of Taipei. My theoretical knowledge takes another blow here. There really are tea shops every step of the way and most are also linked to a small manufacturing operation. But both are far from being picturesque. The selection of teas is varied, however… As I learn here, processing the local teas Long Jing and Bi Luo Chung is still in its infancy. Moreover, they are far, far from reminiscent of their Chinese brothers. Neither their appearance nor their flavor has anything in common with the latter, and the price is dear. I obtrude into the back part of the dwelling in order to see the production itself, and I am surprised. After withering, the tea leaves are thrown by hand into a rotating drum, which is heated from below either by gas or log fire; inside, the tea leaves heat up quickly on the hot walls, killing the eventual possibility of subsequent fermentation. Then they are poured into a small roller, where they are kneaded by the gyrating motion until they take shape of small rolls. After that, they are dried in a conveyor-belt dryer.

But all the sudden I notice that the man of the house is bringing just-withered tea leaves and tossing them in the roller without pre-heating them. “And what is that supposed to be?” I asked, just in case he hadn’t made a mistake. I pleasantly surprise him with my question. “Yes, you’re right, I didn’t heat it up intensely first, but put it directly into the roller. That’s because it’s a different tea. Now I’m making Bao Zhong.” I grasped that here they carefully observe the technological differences between how each tea is produced, nevertheless, in the end all the teas taste very similar. I bet that with blindfolded eyes the producer himself would not recognize Bi Luo Chung from Long Jing (which is not shaped in a roller, but in a type of tub, were it is buffed flat with special brushes). And the locals consider Bao Zhong – here’s the surprise – to be a green tea! I, however, know it is the least fermented oolong around, but I don’t want to trouble them. It would seem rather inappropriate for a Czech tourist to point out to a Taiwanese teaman that he was living in delusion.

The Same, Yet Different

I am headed straight to the heart of the tea industry, to the village of Luku, which lies directly under the “FrozenPeak,” or Tung Ting in Chinese, which lent its name to the most famous Taiwanese tea, and I’m looking forward to some hiking. Under the term “tea industry” one would be wrong to imagine huge factory halls. Tea as exceptional as Tung Ting can only be produced in small amounts and with the irreplaceable human touch. My first steps lead to the seat of the Association of Tea Plantation Owners in Luku. A good move. Secretary Mr. Tony Lin takes me in and tells me exciting news. At the end of the week, I can attend (only as a viewer of course) a tasting of five thousand samples of Tung Ting. The idea actually panics more than pleases me. I can not imagine tasting 5,000 samples of one type of tea, or even why to do it all. But I do suspect this giant-scale tasting has something to do with the tea trade itself.

The village of Luku stretches along a road at the base of a massive mountain crest with peaks over 3,000 meters above sea level, which crosses through the middle of the island. At first glance, the village is nothing extraordinary: the usual houses that can be seen all over the island, tropical vegetation, bamboo groves, and thin betel palm trunks towering to the sky. But what is different from other villages is the amount of tea shops lining the streets. Even in hotel lobbies there’s always room for a tea corner, and, if you ask, the personnel will give you a sample of tea from the canisters on display. I lose no time and take a seat at the table – a stump – and choose a tea. But there’s nothing to choose from. I can either have Tung Ting, i.e. tea grown in the nearby mountains, or Kao Shan, i.e. tea grown in the nearby mountains (but different ones). “I’m completely flummoxed!” They look exactly the same, but take note – even dry, each smells completely differently. “I think I’ll have both,” I tell the lady working at the reception desk, which causes her some inconvenience because, in a word, two teas can not be prepared at the same time in a Kung Fu set. The continuing stalemate is resolved by Tony, who puts both samples in a bag, loads me in his car, and takes me off to the mountains.

“I guess we’re off to Tung Ting Mountain,” I think to myself, “where else could we be going?” The car climbs narrow hairpin turns, all around us thick vegetation thrives. After an hour-long journey the bamboo and pine groves recede, and I can see something I honestly did not expect. If there is a heaven, it must look like this. Azure blue sky and majestic mountain peaks, silvery opaque clouds, and fresh green tea gardens. This place is called Long Fon Sai, or “Valley of Dragons and Birds.” The quietude is only disrupted by whispering winds blowing through the tea plant leaves. The multicolored dots in the distance between the rows of tea plants signify that the harvest is in full swing. But I am already being welcomed by the manager of the local tea processing operation, who invites me into his office. That is where we’ll have the tasting, I learn from Tony. I pass by the now well-known “horn-shaped” machines, drums, conveyor-belt dryers, and stretched out nets with leaves, which are just starting to wilt. The production process for Tung Ting is identical to the production of Tie Guan Yin. Tung Ting, however, is not dried as intensely in the final phase. Hence, it does not take on that lightly over-roasted flavor typical of Tie Guan Yin. Tung Ting is graced with a different characteristic flavor. It sounds incredible, but you can actually trace in it lilac and peony blossoms! Even though those plants are not found in the vicinity at all.

That Tea’s a Demon!

My taste buds are swimming in a sea of flowery fragrances when all the sudden – this sample is totally different. Instead of flowers in the sip, I find the sweetish hint of cream. Now what’s this? “A sample of Kao Shan,” I’m told. So the manager really did prepare the samples brought from the hotel reception. I am spirited away by the unusual flavor and pump my hosts for how it is achieved. I have no idea whether the tea isn’t aromatized or perhaps mixed with something. “No, no, the whole secret lies only in the processing technology and in the type of tea plants in the garden.” I suspect the tea industry in Taiwan is, just like other industries here, highly technologically advanced. That is why I am not at all surprised to learn that cloned TTE 27 tea plants are used for Tung Ting, which guarantee its flowery fragrance. Science is science. To produce Jin Xuan, as the creamy-flavored one is actually called, TTE 29 clones are cultivated. The commonly used name Kao Shan means something like “mountain tea” and does not denote a concrete type of tea. I fancy asking more about the uniqueness of Jin Xuan, but from the tone of the answers of my hosts, I gather it is not an appropriate theme. And why should it be when they don’t have it here and they probably don’t know how to produce it. To sort the thoughts in my head and clear the matter up, I pose the last question. “So why don’t you have it here, too?” I ask, feeling rather impertinent. Tony fields the question and explains: “Among tea experts, a flowery fragrance and flavor is commonly better rated than creamy. In a flowery undertone, one can find many more fine nuances and revel in comparing the most various flowery bouquets, of which there are thousands. But there is just one creamy character. Unless you know more creamy scents and can describe them?” he drove me into a corner. “All right, so I won’t ask any more questions,” I tell Tony, accepting his explanation. But my head is still churning with doubt. How many people in the world have come so far in recognizing flavors in tea that they are aware of the flavor undertones with traces of fragrances of lilac or violets? My preoccupied expression did not go unnoticed by the manager, who turned to me and said, “I’ll divulge something to you. That tea’s a demon! That has been tested by time and you, too, will figure it out in time. Jin Xuan is a tea with a very intoxicating flavor and fragrance, and it conquers everyone immediately. You’ll return to it with unusual zeal. You’ll have the feeling your desire for it is never satiated. And suddenly, in one go, that will come to an end. That tea will suddenly, overnight, abandon you, you’ll lose all interest in it! Not only that you won’t have a hankering for it, but the idea of drinking it may even arouse unpleasant feelings. It’s a tea of two faces. It is a tea like night and day.”

Well, that’s really what I needed to boost my already quite eroded self-confidence that I’ll ever understand Taiwanese teas. Tea – demon!

A Lake Can Not Have a Peak!

Communicating in English is not always ideal in areas not visited by hordes of tourists. I noticed that my guide Tony answered some of my questions noncommittally and others not at all. That’s why I did not, for example, learn if any of the peaks surrounding us while visiting the tea gardens was Tung Ting. No other choice but to ask again. “Of course it wasn’t,” replied Tony Lin. “We’re going there now,” and he instructed the driver, who set off on a road which descended down the slope. “Oh great, looks like I’m in for another trip,” I thought to myself, when I realized that, laid out before us, was a valley on the bottom of which floating clouds reflected on the surface of a large lake. “I guess we’ll have to climb the opposite mountainside, which will be a long journey. And so we’re stopping in some wayside inn on the lakefront to gather strength for the hike,” I told myself as we got out of the car and Tony uttered: “So we’re here.” I look around and assure Tony that it is indeed lovely here. “Well, enjoy it, you’re not in Tung Ting every day.”

First the “tea demon,” then the elevated plateau with a lake called “Frozen Peak” surrounded by mountain crests. I could not have asked for more good news. “And how many days a year does it freeze here?” I direct my question at Tony. “Not even one. Our tea plants would freeze.” So, thanks a lot, Mr. Secretary, for the information. As soon as you want to tell me that “cat” means “dog” in Luku, you’ll find me in my hotel. Or even better, don’t look for me at all around here. I’m heading to the south.

Don’t Lie on the Beach and Don’t Go in the Water

I have a feeling my brain hard disc is completely full of information and it’s time to perform defragmentation. Which is why I’m setting off to the south of the island to the city of Kenting, which is renowned as a resort with beautiful beaches, a place where one can relax and clear one’s head without disturbances.

I settle in to a hotel in Nan Wan Bay, near a small inlet lined by the throbbing colonnade of a picturesque town, and I’m relishing in it. Although it is warm, even hot, and the water in the sea is warm, I can’t see even one deck chair or blanket on the beach. Fantastic! I don’t pay much attention to the approaching group of students – almost all wearing three-quarter length pants, t-shirts, short cotton jackets, hats or baseball caps. I spread out my beach towel, strip down to my bathing suit, and lie down. Now I’m not sure whether I laid down on the sand too quickly or clumsily from joy or fatigue, but what I do remember for sure was the group’s quick reaction. They head straight for me, their spokesperson leans over and asks me if I don’t feel sick. “No, no, I’m fine. I’m resting and hoping to work on my tan,” I say, turn over on my stomach, and live in the hope that that is the end of that. But the muffled laughter behind me signalizes something else. “Can we take a picture of you?” I can’t believe my ears. They continue, “Nobody back home would believe us if we told them you were lying right here but nothing was wrong with you.” At that moment, I notice a little detail. Some of the students are wearing over their cotton jackets little backpacks with their personal things. No, I haven’t gone nuts. That’s how it works here. As I later learned, bathing and swimming isn’t in style, people rest at night and in bed, and those with tans are revealing their lower-class background or even that they are manual or peasant laborers. And those who just want to refresh themselves don’t take their backpacks off or even strip down just to wet their lower limbs. Such is custom.

I run into the sea and, with a long crawl stroke, swim further and further away from the shore. The figures in light-colored clothing on the shore get smaller and smaller. Luxuriating in the waves, I slowly start to return to the shore. The figures on the beach become increasingly distinct. They’re gesticulating at me wildly. “I guess they’re waving goodbye,” I tell myself, and wave back at them heartily with both arms. And just then I notice the colored buoys, which, located about 30 meters from the shore at a depth of maybe one meter, clearly signalize how far out swimmers can go. My waving from more than 200 meters has obviously been interpreted as a call for help. A shore patrol jet ski approaches. How embarrassing! I refuse to get on board and proudly swim to shore, escorted by beefy Taiwanese lifeguards. A crowd of fifty or more is waiting on the shore and it keeps growing. I don’t know if this custom of welcoming swimmers is widespread in Taiwan or whether it has deeper historical roots. I was, however, given a royal welcome. Slaps on the shoulder, photographs with the local beauties (I mean those in the jackets and life jackets), and an unceasing stream of questions – why did I do it? What was I trying to prove or suggest? At that moment, I recalled a scene from a very charming and human film, “Forrest Gump.” One day Forrest decides to literally run across America, and by personal example he sets a huge movement in motion. That thought took me aback for a second. All it would take is to add a little political or social subtext to my answers, and I would surely have followers immediately.

“No, no, no, my friends. Nothing exceptional. I’m lying on the ground because I want to rest; it’s no fun in the hotel bed. I’m sunbathing because I know that I won’t get a tan anyway in the two days I’ll be here, and I swam so far only so I’d know that you won’t forget me, and that you’ll follow your dreams. Thanks for your attention,” I take my beach towel and head to the hotel. A bus full of tourists interrupts my musings when it slows down next to me and I become the target of camera lenses aimed from the bus windows. And why not – I am, after all, walking down the street in nothing but my swimming suit! “I’ve perplexed them all,” I tell myself, “tomorrow I’m going back to Luku!”

Once the Lid Turns, You’re Out!

From the morning hours, the atmosphere around the headquarters of the Association of Local Farmers is festive. And why shouldn’t it be when everyone has been waiting for this day all year long? Delegations are arriving. Not official ones, with high-level public servants. The delegations are from various countries in Europe, America, and even nearby Japan, comprised of merchants and their tasters, as well as little groups of lovers of good tea. The moment the samples from local farmers (and in fact not only from them) start accumulating in Luku, it is a holiday. The contest that was started in 1976 by Mr. Kuan Yen Lin, today its general manager, already has a reputation that spills beyond the region’s borders. It could be considered the climax of the whole harvest of partially fermented teas in Taiwan. Once the samples have been turned in, the result can not be influenced and there is no choice but to wait for the jury’s verdict.

The only problem is, Tung Ting is the only tea tasted and judged here. If another type of tea is harvested and processed somewhere – tough luck.

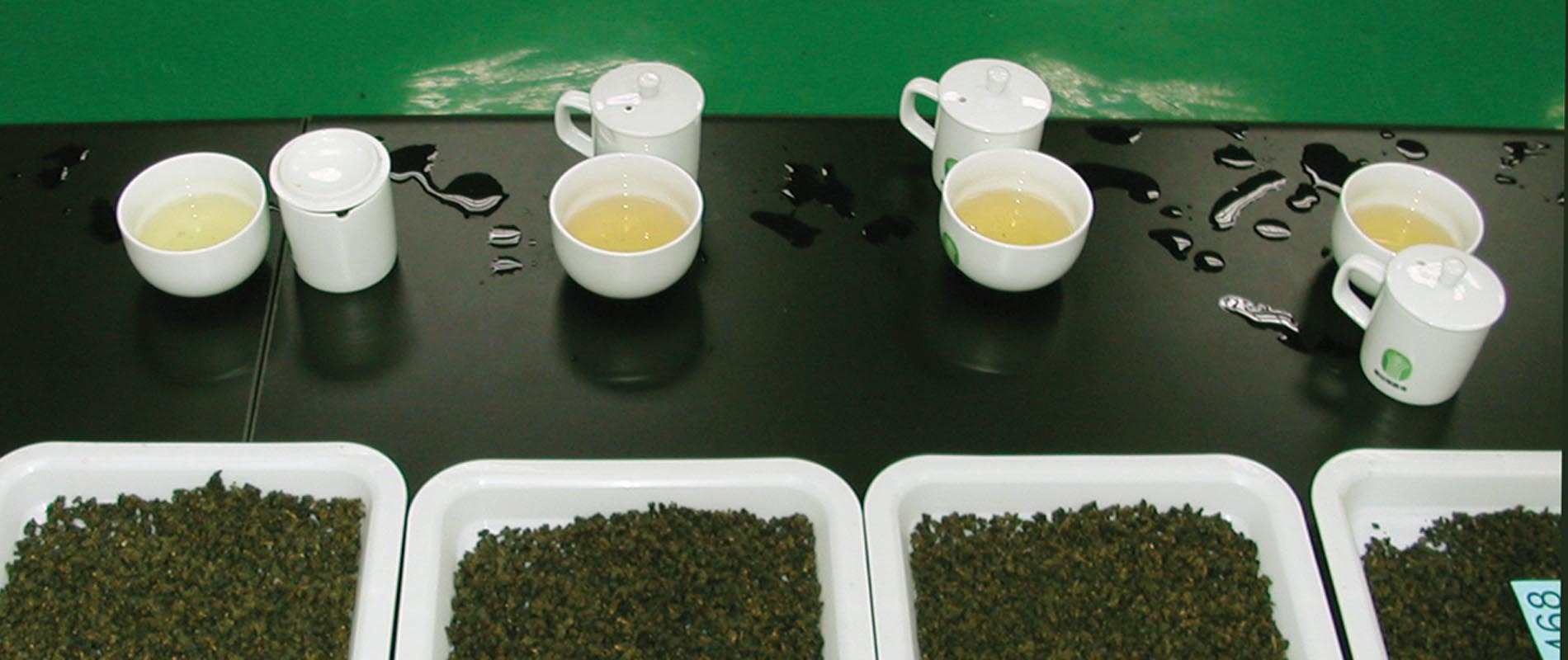

In the back part of the association’s headquarters is a large parking lot. On this important day it is filled with cars. Each may be hiding a real treasure in its trunk. That treasure is of course Tung Ting. The condition for entering the contest is delivering twelve catties of tea (one catty equals 600 grams). But each producer can enter as many different samples he wants. And so there can even be 4,000 samples entered in the contest! In 2006, there was a record 4,822 samples! One catty of tea is divided into three samples, where the first and second are used for tasting and the third for comparison with the tea which is sold at the market, which closes the festival after the winner has been announced. One catty belongs to the contest organizers. The competing teas are poured into universal red containers, carefully weighed and tagged with a number, which is hidden inside the tea and must not be known by anyone other than the recording clerk. In the throng of samples, the clerk barely has time to record them in the registration book, let alone remember which is which, so anonymity is thereby guaranteed. That is surely safeguarded with other measures, but those weren’t discussed even during the lecture held inside the association’s headquarters.

Among other things in the association’s seat is a lecture hall with various information panels from which the visitor can learn everything about the history of tea and how it is produced in Luku. There are also a number of various historical artifacts and sketches recalling the trailblazing efforts of tea pioneers. One fact worth mentioning is that Tung Ting was not kneaded in horn-shaped motor-driven machines in bygone days, but in a much simpler way – by foot! The farmer simply wrapped the tea in tarp, hopped on it, and treaded…

But I was most interested in how the tasting itself was organized. After all, tasting more than 4,000 samples is no funny business.

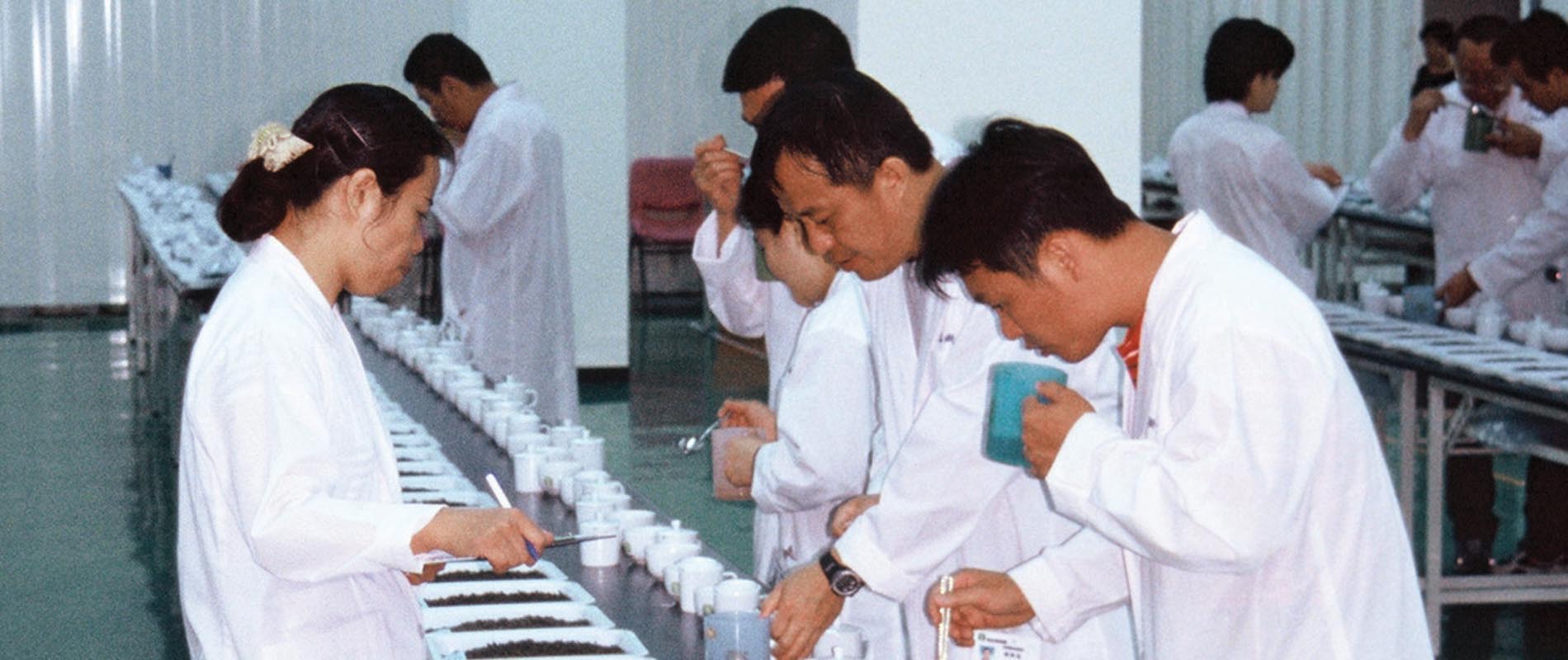

“We establish five five-member tasting teams from selected and experienced experts, which then taste the prepared samples. It is important for the team to agree on every tea and mark it accordingly. Each team has more than 35 samples, prepared by assistants, before it at a time. All five team members taste the samples in order, and the fate of the tea is decided by the tasting cup’s placement in relation to the bowl and by the position of the lid. When the cup is at twelve o’clock position, it indicates the greatest success. A cup at three o’clock means commendable, at six o’clock means good, but nine o’clock – watch out! That means the lid is even turned around next to the cup! And that’s a sign that the tea is out of the contest,” Tony clarifies the system of judging the competing samples. The contest itself lasts several weeks and each team gradually gets to taste each tea. The results are then evaluated, and those with the same number of points are tasted over and over again anonymously, until the contest is decided.

12 Kilos for the Winner

The day all the results of the contest are announced determines the pricing of tea in the broader area for the entire next year. On that day, not only does one of the participants become the winner and the bearer of the title “Champion No. 1,” but, according to the contest rules, he also gets to sell 20 catties (12 kg) of his winning tea at the festival’s market, which follows immediately after the results have been announced. In the last auction, the price of the winning tea reached an unbelievable USD 400 per kilogram.

Roughly 2 percent of the samples (appr. 80 entries) obtain the title “Tea No. 1” and their producers are rewarded with the chance of selling their 12 kilograms for up to USD 100/kg.

The third place gains the title “Tea No. 2,” which around 5 percent of the judged samples win.

Fourth place, which up to 8 percent of all competing teas are rewarded, receive the title “Tea No. 3.”

Another 15 to 20 percent gain the right to use the mark of three plum tree blossoms on their tea, and the remaining 30 to 40 percent are eliminated from the contest.

So it is more than obvious that the tea producers prize a good evaluation for the next tea season and how they use it to set the price of their products. After all, it is logical that whoever who can pride himself on a title acquired in the contest must know how to produce tea, even for the rest of the year. And he also deserves to be paid well for it.

And so once the contest in Luku has ended, the winning tea becomes not only the envy of local merchants, but also the product setting the quality bar for the whole season.

In silent astonishment I listened to Tony’s interpretation of how sweet victory can be, and after it I yearned to taste at least one of the teas vying for glory in the contest. I unobtrusively asked Tony if I couldn’t enter the tasting room and take a few pictures. Albeit unwillingly considering the tasters’ concentration, he agreed. I hastily took a few pictures and swarmed over to the table with already judged samples and asked Tony if he wouldn’t take pictures of me with them. Feeling like a king, I lifted the cup of still warm liquid to my lips and sipped. I was overcome by a rapturous feeling, then a quick flash of the camera, and we scramble out. Quite an experience. “It was the last sample on the first table,” I told myself as I exited, “I’ll never forget it.” Only when I got home and browsed the photos did I realize that “my” sample had been eliminated from the contest – the lid was inverted…

So How Did It Start?

I’m sitting in a bus, parting with Luku, and ruminating over everything I experienced on that small but gorgeous island. I saw the production of green tea that isn’t green. I took delight in gorgeous mountain views and incredibly beautiful tea gardens on their slopes. I went swimming and thereby caused a riotous assembly. I met lots of nice people and I basically had no negative experiences during my entire stay. I learned about tea which they say is a demon, and I discovered the secret of the fragrance of Tung Ting. The only thing I regretted was the ‘FrozenPeak’ itself. “That just isn’t possible,” I told myself. “I visited a peak that wasn’t even pointed. It was rather flat, and a lake was on it! And it reportedly hasn’t even ever frozen over up there! That’s just strange.”

A fluke was needed. When changing buses, I had to go from one bus station to another. On the way I got a bit lost, but I was taken in by an amiable young lady by the name of Katy, who was also traveling from Luku, going in the same direction as I was, and accompanied me to the right bus. I was so overloaded with impressions that I had to tell her about everything I encountered in Taiwan. “They are all big mysteries to me and one day I’d like to get to the bottom of them,” I told her. As is my custom, I presented Katy with my business card.

When I returned home, I almost forgot about the brief encounter. But one day I came into my office and discovered an envelope that was, according to the characters (I mean the Chinese characters), from Taiwan. I opened it up in suspense and removed two snapshots. On their backside was a friendly greeting and two words: “snow-covered gardens.” At that moment I realized I was finally holding evidence in my hands. Even the locals couldn’t explain to me why that special place is named “FrozenPeak.” But now I know what many don’t – that sometimes far up there in the mountains, where nobody goes in the winter, where only birds, and possibly even dragons, soar during that sad season, something white and damned cold swoops down from the skies. But ever so briefly…

And so I don’t want to ascertain any more details or dissect the local vernacular. It is so lovely to let yourself ride the waves of legends and myths or revel in the notion that there, somewhere above, fly dragons above snow-covered tea plant beds. Who cares if it’s really otherwise?

Written by Jirka Simsa in Fall 2006